A film history intermezzo

In the summer of 1912, Denmark's first cinema director, Constantin

Philipsen (1859-1925), as previously referred to as the large platform hall

in Copenhagen at the time, rented the second central station and had it

converted into Europe's largest cinema theatre with room for 3,000 people. The

cinema was given the pompous name PALACE THEATRE. The inauguration took place

on October 17, 1912, and the premiere film was the German "Children of

the General", which, however, was directed by the Danish film director

Urban Gad (1879-1947) and with Danish Asta Nielsen, who was then married

to the film's director, in the female lead. Among other things, a French play

and a French farce were also shown, as well as a so-called Weekly Journal. On

the same occasion, a so-called Orchestral Concerto was held under the direction

of Conductor Fr. Schnedler-Petersen, whose 30-piece orchestra also

accompanied the films shown, which were actually silent films, as a workable

tone film system had not yet been invented. Edison's Phonograph was too

cumbersome to synchronize with the film, which often risked breaking, which is

why the damaged piece of film was cut away, but in doing so the original

synchronicity between sound and image was broken, and therefore for the time

being abandoned the use of this system. As well as this film as the later films

that were on the program in the Palace Theatre became a huge success and the

money flowed in to its originator, who invested in the creation of an entire

cinema chain across the country. But the cinema had to cease in February 1916,

when the demolition of the old railway station began. However, Philipsen sold

the name "Palads Teatret" to a group that wanted to build a brand new

and more modern, but also huge cinema building on an area close to the

demolished makeshift former cinema. Philipsen, in turn, put money into the

construction of a large cinema, which was built on the corner of Gl. Kongevej

and Værnedamsvej, and which was inaugurated in September 1918. The new grand

cinema was named Kino Palæet, as previously mentioned here in my

autobiography.

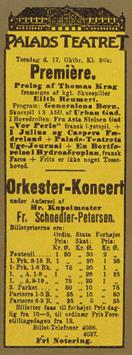

Left:

Advertisement for the Palace Theatre's opening performance.

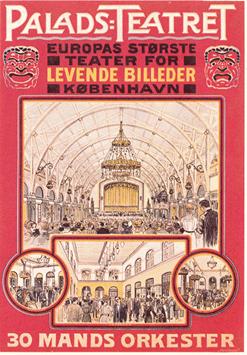

Right: Poster for

palads Teatret, Europe's largest theatre for moving images. A 30-piece

orchestra provided the musical accompaniment of the silent films. © The Danish

Film Museum's Picture Archive.

Constantin Philipsen was an early move in the Danish cinema industry, as he

already in 1902 established his first cinema, Odeon Teatret, on

Frederiksberg Allé. The name "Odeon" probably originated from

Frederiksberg Morskabsteater's past as the music and beer hall

"Odeon". Philipsen later used the name for his cinema on Fælledvej in

Nørrebro, which many, many years later would become one of the cinemas where my

cousin, my comrades and I regularly came. However, the audience failed

Copenhagen's probably first suburban cinema, which therefore had to close after

six months. However, this did not knock Philipsen out, as in 1904 he

established Copenhagen's first permanent cinema, Kosmorama, at Østergade

26, and in the following years he opened similar cinemas under the same name in

virtually all major Danish cities, just as he also established several cinemas

under other names in the capital. The films were, as was the case abroad,

accompanied by piano music and in some cases also by various sound effects,

performed by the pianist and his eventual assistant.

The first "talking movies"

However, the cinema magnate aimed higher, and in 1906 he was able to

present in Kosmorama a "talking film" according to Edison's

principle, having bought in Berlin "The Merry Widow" with

accompanying gramophone waltzes. It was a bit of a Copenhagen event that

received praise in the newspaper. In 1908, however, Philipsen sold Kosmorama to

Hjalmar Davidsen (1879-1958), who partly became director of the cinema

and partly set up a production company, Kosmorama, with the aim of producing

films himself. In 1910, the company produced its first feature film, "The

Abyss", written and directed by Urban Gad and starring Asta Nielsen and

Povl Reumert in the two leading roles. Philipsen, meanwhile, had been granted

permission to open several new cinemas in the capital, "Royal

Biografen", established in 1906 at Vesterbrogade 34, and "Standard

Biograf", established in 1908 at Falkonér Allé 73. The latter existed

for many years, and existed both during and after World War II and even further

ahead. It was one of the Copenhagen cinemas, where I regularly came as a big

boy and young man.

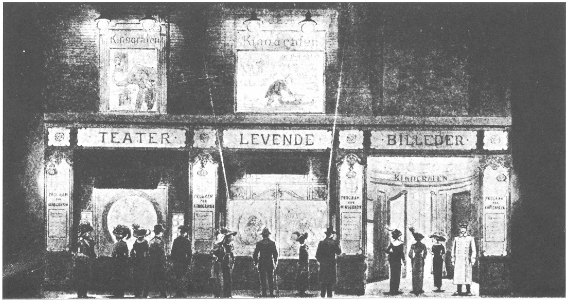

Cinematographer

Peter Elfelt's first cinema was located at Frederiksberggade 27 on the first

floor. However, it was given a short lifespan due to failing audience interest.

After half a year from 1901 to 1902, the cinema had to close with a large

deficit. However, Elfelt did not give up, as four years later he opened KINOGRAFEN

in the property next door, namely Frederiksberggade 25. In 1939, Kinografen

closed, but after a rebuilding it was reopened under the name BRISTOL. - The

Danish Film Museum's Picture Archive.

Philipsen's Odeon Cinema in

Vesterbro was not, however, the first cinema in Copenhagen, as court

photographer Peter Elfelt (1866-1931) had already opened the

Kinografen on the first floor of Frederiksberggade 27 in 1901, but after

half a year of deficit it had to close in 1902. However, this did not make

Elfelt, who was the first in Denmark to film himself, lose his courage, as in

1906 he became co-owner of a new Kinografen, which was housed in the property

next to his first cinema, namely in Frederiksberggade 25. This cinema was

lucky, and it existed for many years, and was, as previously mentioned, one of

two cinemas in the capital, which both in the spring and around Christmas time

showed a program consisting of six of Disney's short cartoons with the

well-known characters, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, Pluto and others. In

1939, the Kinograph changed its name to the Bristol Theatre, and as such

the cinema existed until competition from the new mass medium, television,

became too fierce and it had to close. It happened in 1966.

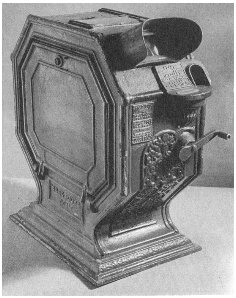

Above are the famous American inventor Edison's two devices for sound and

image from 1905, respectively called the phonograph – the precursor of the

gramophone – and the kinetoscope. The latter was at that time hand-operated,

and by a special device Edison had succeeded in synchronizing the two

apparatuses so that image and sound were performed simultaneously

(synchronously). However, the system had several decisive drawbacks, and

therefore was soon abandoned in practice. This meant that the film remained mute

until a more reliable and secure sound-picture system took hold in the late

1920s. - The Danish Film Museum's

Picture Archive.

Probably inspired by what he had seen of films in Pacht's Panorama &

Panoptikon, Elfelt began producing and shooting films himself as early as the

autumn of 1896, films that he gave the titles "Asphaltlayers",

"The Fire Brigade Moves Out" and "The Swans in Sortedams

Lake". Already in January 1897, these films were included in Pacht's

performances at the Town Hall Square. Elfelt also shot ballet films and was the

first in Denmark to make an actual feature film, "The Execution",

1903, with Francesca Nathansen in the female lead. Thanks to royal court

photographer Elfelt, today we have vivid images of King Christian IX and Queen

Louise and their children, in-laws and grandchildren. Among the children Frederick,

the later King Frederick VIII, who married the Swedish Princess Louise,

Alexandra, married to the English Queen Victoria's eldest

son, Prince Albert Edward, the later King Edward VII, Dagmar, married to the Russian Grand Prince Alexander Alexandrovitsch, the later

Tsar Alexander III. Alice of Hesse, and

their four daughters, Olga, Tatjana, Maria, Anastasia and only son, Nicolai, in

1918 brutally murdered on the orders of the leader of Russia's new

revolutionary rulers, Lenin.

This sketch of Storm P. in the

theatre magazine Masken, is supposed to represent the early beginnings

of the Danish film company, which later became world famous under the name Nordisk

Film. However, the drawing should

probably be perceived humorously, because the plot on Mosedalvej in Valby that

Ole Olsen acquired in 1906 was somewhat larger than the drawing shows. The area

was soon expanded by the purchase of adcumbent plots, so that Nordisk Film

already around the beginning of World War I consisted of a total of four

scenes, namely scenes 1, 2, 3 and 4. In 1915 the company's largest studio,

called stage 5, was built, and this, unlike the previous ones, was furnished

for recordings both in daylight and artificial light. - The Danish Film

Museum's Image Archive.

Ole Olsen's Film Factory

The year after Philipsen had opened Kosmorama on Østergade, the film

magnate Ole Olsen (1863-1943) opened the capital's second permanent

cinema, Biograf-Theatret, in Vimmelskaftet 47 in 1905. He was, like his

competitor, Constantin Philipsen, an enterprising, inventive and skilled

merchant, whose methods were authoritarian and could border on the brutal and

ruthless when something went against him. But he had unmistakably

"nose" for the possibilities of the new medium, which he had come to

know during his time as a traveling market entertainer. He was, in short, a man

who had the ability to organize and make money, big money even.

After seeing films at Pacht in

the Town Hall Square and in Germany, he himself began to travel around as early

as 1901 and with varying degrees of luck showcasing films, both at home and in

Sweden. However, he did not give up, but

ended up opening the "Copenhagen Cinema Theatre", later simply called

"Biograf Theatre". Ole Olsen's big problem, however, was to get

enough and good films for screening in his cinema, especially since Constantin

Philipsen had already secured some of the best deliveries from France, England

and America.

However, Ole Olsen and his people

must probably have been inspired by Elfelt's attempts as a film producer, and

Ole Olsen therefore already in 1905 hired a professional photographer to help

him, and then they started shooting films themselves, first and foremost for

the newly opened cinema. In 1906, the new film producer saw the chance to

acquire a spectacular and highly topical reportage when King Christian IX, who

died on 29 January of that year, was to be buried. Ole Olsen managed to secure

the exclusive right to film the outdoor part of the event when the king was

buried in Roskilde Cathedral. It was then not possible to film indoors due to

the lighting conditions. In addition, he and his people shot the reportage film

"Frederik the 8th's Proclamation", and the two films naturally became

run-ins in the cinema in Vimmelskaftet, which is why the money from the ticket

revenue almost poured in.

After this successful and

successful start-up, Ole Olsen very much wanted to continue as a film producer,

but as such you had to have a production company and a name, and it was

initially "Ole Olsen's Film Industry" or "Ole Olsen's Film

Factory", whose address was the same as Biograf Theatre's, namely

Vimmelskaftet 47. In addition, it was important to have a trademark that could

identify and protect the company's films from confusion with other companies'

films, especially on the world market, and which could ensure that the audience

recognized and had confidence in the company behind it. It was the company's

then office lady, Ms. Gundestrup, who suggested that the trademark could be a

polar bear standing on a globe. In the following period, this mark was not only

used on the film's pretexts and intertexts, as these could risk being damaged

during the screening and consequently cut away, so therefore the trademark was

also placed in many places in the film itself. The trademark was painted on a

large cardboard sign, and it was placed in the film's decorations or wherever

there was room for it. The trademark with the polar bear on the earth ball was

used from 1906, but it was not registered until 1909. In September 1906, the company

changed its name to the then famous Nordisk Films Kompagni, but the

company's official birthday is November 6, 1906, as the citizen letter from the

Copenhagen Magistrate was first drawn up on this date, and it is therefore

considered the company's founding day.

The Danish commercial film pioneer Ole Olsen's cinema in Vimmelskaftet

47. It was opened under the name Biograf Theatret as Copenhagen's second

permanent cinema on 23 April 1905. But already the following year, Ole Olsen

handed over the management of the cinema to one of his employees, Niels le

Tort, who from 1907 onwards also took over full ownership of the cinema. - The Danish

Film Museum's Picture Archive.

A diligent film producer

In the following time, Ole Olsen, together with his employees, produced a

number of small films of current events, nature films and small dramatic and

comic episodes. However, Ole Olsen was not only an enterprising and diligent

producer, but also a good merchant who knew how to devote his films, partly to

Danish and partly to foreign cinemas, mainly in Germany.

As mentioned, Ole Olsen first

and foremost understood how to do business, and already in the autumn of 1806

he left the operation of the Cinema Theatre to his co-director, Niels le Tort

(1855-1924), who from 1 January 1907 became the owner of the cinema. Ole Olsen

had so far withdrawn from cinema operations and concentrated on his great

ambitions as a film producer. According to Storm P., who for some years from

1906-08 was involved both as a cartoonist, writer and actor in the film mogul's

enterprise, Ole Olsen bought an allotment area on Mosedalvej in Valby in the

summer of 1906, and here they intended to record the company's indoor scenes.

Indoor scenes are so much said,

though, because because of the film negative's demand for relatively bright

light to be exposed, you couldn't film indoors back then. There were not yet

electric floodlights that provided enough light to illuminate a room

sufficiently for decorations and actors to be clearly visible on the film

strip. Decorations were therefore painted on heavy paper or canvas and placed

in the open air, preferably in the hope of sunlight and in constant fear of

strong winds or rain. This is one of the reasons why on some silent films you

can often see that the wind or wind makes itself undesirable, for example by

the tablecloth on the living room dining table hanging and fluttering, or by

the newspaper lying on the table flipping by itself.

In this scene

photo from the film I Bondefanger claws (1910), it is clearly seen that

the decoration is built up on a wooden floor. When it came to utilizing

daylight, there was neither a wall nor a ceiling on the decoration. - © 1977

Marguerite Engberg: Danish Silent Film I, pp. 107-08. Rhodes Publishing

House, Copenhagen 1977.

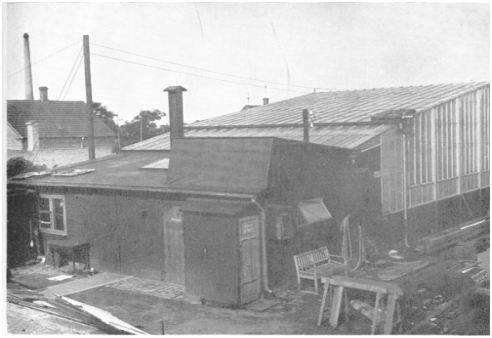

Nordisk Film's

scene 1, as it looked in the silent film era. In order to make the most of the

sun and daylight, the studio itself is located with its glass walls facing

north and side walls to the east and west, respectively. The wooden building

behind is located on the south side of the studio. At the back of the picture

is taken by a couple of the private residential houses, which for many years

were located on Mosedalvej. - © 1977 Marguerite Engberg: Danish Silent Film

I, p. 111. Rhodes Publishing House, Copenhagen 1977.

However, an aim was soon to

improve the shooting conditions, especially by erecting a wooden shed and, in direct

connection to this, a studio with glass walls and a glass roof, so that the

sunlight could still be exploited. But the bothersome wind and rain were

avoided. At the same time as filming using sunlight alone, artificial light was

also tried, but it did not succeed very well at first. This studio was and

still is to this day referred to as Scene 1, as the building, which is probably

the world's oldest existing film studio, is still preserved, and which after a

number of years of being used for magazines has once again been used as a

studio, mainly for recording intimate TV programs.

In 1909 a new and larger studio

was built on Mosedalvej, and it was consequently designated as Scene 2. But as

production increased, this studio was not sufficient to meet the demands, and a

new and even larger studio, Scene 3, was built in 1911. The building is on two

floors, of which the brick lower floor was furnished for magazines and

wardrobes for the actors, while the stage space itself is located at the height

of the first floor. During the spring of 1912, an open open open-air stage was

also set up, where the many circus films the company produced at the time were

shot.

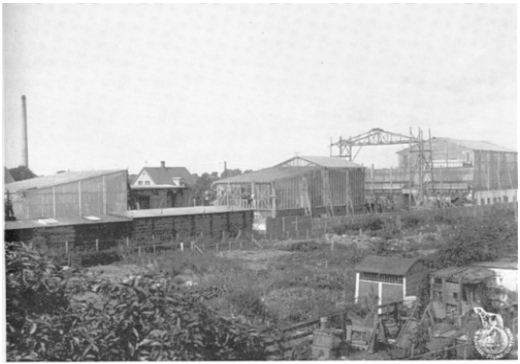

A view of

Nordisk Film seen from the northwest. This is what the studios looked like

shortly before the outbreak of World War I. In the foreground are still the

remains of the allotment area on which the studios were built. It is scene 1

that is seen on the far left, while the slightly larger stage 2 is seen in the

middle of the picture, and the big scene 3 is seen on the right. In front of

the latter, scene 4 is under construction.

- © 1977 Marguerite Engberg: Danish Silent Film I, p. 109. Rhodes

Publishing House, Copenhagen 1977.

Scene 4 was added in 1914, and

it was actually a completed studio, which was originally built for O. E.

Nathansohn's film company, Lille Strandvej in Hellerup. But when Nathansohn's

company collapsed during the autumn of 1913, Nordisk Films Kompagni bought the

studio and had it transported to Mosedalvej, where it was erected. Finally, the

last and largest studio, called Scene 5, came into being in 1915, and it was,

unlike scenes 1-4, partly intended for artificial light shots. This studio was

built on some newly acquired allotment plots that were neighbouring plots to

those previously acquired. Here was also built a wooden barrack, which quickly

got the name "Poet's Workshop" because it was used by the so-called

dramaturger, i.e. people who processed and rewrote submitted manuscripts or

synopses, novels and short stories into the so-called screenplays, which were

used as the basis for "turning" the films, which were then performed

by hand, both during the filming and during the screening.

In the mentioned "poet's workshop" worked for a while the later

so famous film director Carl Th. Dreyer (1889-1968). He was trained as a

journalist and as such had been employed at Berlingske Tidende 1909-10,

at the daily newspaper Riget in 1912, and in the same period he

regularly delivered articles to the weekly magazine Illustreret Tidende. On 1 July

1912 he was employed at Ekstrabladet, and here, under the pseudonym

"Tommen", he also began to write about many other subjects than

aviatics, including films, which would soon become a prominent area of interest

with him. This interest led, among other things, to the fact that in June 1913

he was employed as a dramaturg at Nordisk Films Kompagni on Mosedalvej, where,

as mentioned, he came to work in the "Poet Workshop", where a number

of other more or less excellent playwrights were also employed, partly at the

same time as Dreyer and partly later.

"Down with the weapons"

It is probably characteristic of Dreyer that one of the novels he strongly

wanted Nordisk to film was "Down with the Weapons", which in 1905

obtained his authoress, Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914), the Nobel Peace

Prize 1905. The novel's highly pacifist tendency was prevalent in cultivated

circles both in militant Germany and the rest of Europe, and not least in

Denmark, which did not want a repeat of the defeat of 1864. Pacifism had again

become prevalent in some circles in 1913, when looming war clouds again pulled

up over Europe and ended with the outbreak of World War I, which began

September 3, 1914. Dreyer adapted the novel into feature films, and as a

director Holger-Madsen (1878-1943) was chosen, who in the years 1913-20

was associated with Nordisk Film as a writer, director and actor.

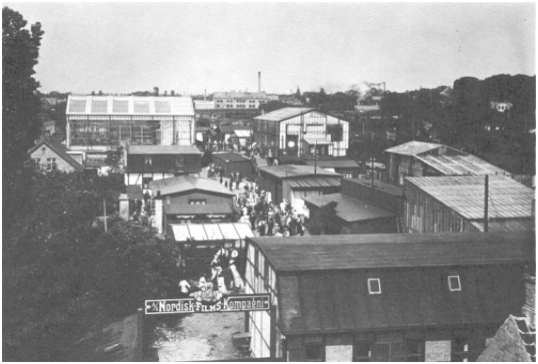

Above is a

view of Nordisk Film's area and buildings in 1918 with the then four studios.

The picture was taken from south to north. In the foreground is the main

entrance with the administration building to the right in the foreground.

Immediately behind his right end is scene 1, and in front of this scene 2, then

scene 3 and – perpendicular to this – the somewhat larger stage 4. Like the

other scenes, it was built as a solid wooden skeleton clad in glass, but its

foundation consisted of a foundation brick building that stretched the entire

length of the studio, which can be seen in the following picture on page 112.

As can be seen from the many people in the photo, the place was a busy

workplace. - The Danish Film Museum's Picture Archive.

However, the film was so current and

realistic in its battle scenes that the film censorship postponed its premiere

in Europe, but it was shown with great success in the United States in the late

summer of 1914. Here its pacifist message came at an opportune time, as large

circles of American society wanted to keep the country out of the fighting.

However, the film was granted permission to be screening in Denmark, but upon

the censorship on 31 July 1914, the film was banned for children. It premiered

in Danish cinemas on 18 September 1915, and then the war raged between the

Central Powers Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey, and the Allies: Serbia,

Russia, Belgium, France and Great Britain with dominions and colonies,

Montenegro, Japan, Italy, and after 1915 even more countries joined. The

economically and militarily relatively strong United States entered the war on

the side of the Allies in April 1917, and this marked a decisive turning point

for the course of the war.

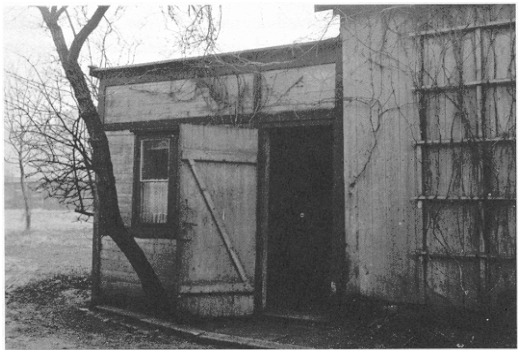

In this photo from 1913, a number of actors or extras are seen in front

of their wardrobes at Nordisk Film. From a personal knowledge of the conditions

on the site, it must as far as I can estimate have been on top of this wardrobe

building that stage 4 was erected in the spring of 1914. What the tree

scaffolding at the top of the picture should serve for, I have not succeeded in

ascertaining. But if it is the wardrobes under scene 4 that are in

question, then many famous Danish actors have had their regular time on the

site since the silent film era and right up to the 1980s. – The Danish Film

Museum's Picture Archive.

For Nordisk Film, "Down with the Weapons" meant an audience and

box office success, which inspired the company to produce more war films, and

in all haste scripts and screenplays were made for a total of four films in

this genre, striving to make especially the battle scenes as realistic and

impactful as possible. These four war films were: The Spy, Pro Patria, The

Robbed Cannon Drawings, and War and Love. The former film

premiered in Germany in February 1915, while the other three did not premiere

in America until the early summer of 1915. The films did not get very good

reviews and none of them became an audience success either. This was perhaps

not least due to the fact that in the meantime a landmark film historical

premiere had taken place in American cinemas, namely The Birth of a Nation

by the master director David Wark Griffith (1875-1948), which premiered

on February 8, 1915. This film, which was about the American Civil War of

1861-65, contained, among other things, some realistic battle scenes and eerie

Ku-Kuks-Klan scenes, which, like the rest of the film, were staged and cut with

such a mastery that the Danish war films had to seem dull, tame and boring in comparison.

But in this sketchy presentation

of Nordisk Film's history, which of course has only an indirect and peripheral

connection to my grandmother's life, but a little more to my own story, we have

not yet reached the outbreak of the First World War. So far, we have only

arrived at the year 1906, i.e. about a few years before my mother was born. So

the Danish film and cinema business was very well underway already at this

early stage of the century. But cartoons had not yet been made in Denmark, but

in England and – of course – especially in America, though not in Hollywood, as

the film city did not exist at the time, but rather in New York.

That film in more than one sense is illusion art shows Valdemar Psilander's

extremely modest and primitive wardrobe, which is still found on Nordisk Film's

territory on Mosedalvej in Valby. The contents consisted of a make-up table

with a mirror, a chair and a wood-burning stove with special space to warm the

feet. The cloakroom building is just behind stage 1 and has been lying unused

since Psilander had his roughly daily walk on the site. - The Danish Film

Museum's Picture Archive.

Nordisk Film in Frihavnen

The technical side of the film production, such as the production, fixation

and copying of the negative film, was in the first beginning made at home in

Ole Olsen's private villa on Kronprinsensvej in Frederiksberg. But the

conditions here were not in the long run suitable for the purpose, and

therefore already during the summer of 1906 it succeeded in adding an

additional address to Ole Olsen's Film Industry, namely Manufakturhuset, 5th

floor, in Copenhagen's Free Port. The Free Port was a customs closed area, so

that the companies that were within its borders and received their goods from

abroad only had to pay customs duties on the imported goods when these were

taken out of the Free Port and into Copenhagen. It had the economic advantage

that customs duties had to be paid only on the quantity of raw film used and

then carried outside the customs guard. And since the film negatives always

remained in the premises of the Manufakturhuset, no customs duty had to be

paid. Duties were also to be paid only on the amount of film copies that went

out of the Free Port, but since the majority of Ole Olsen's film production was

sold abroad, the film copies could therefore be shipped from the Free Port

itself, thus avoiding and saving the company the cost of customs clearance.

However, it must be said that at

first there were many difficulties, and that several meters of positive raw

film went to waste, because the people who worked in the film laboratory in

Frihavn for good reasons did not yet always master the technical sides of film

production. They were relegated to experimenting with workable solutions and

results to the many technical problems that arose along the way.

However, the space in

Manufakturhuset soon became too small for the rapidly expanding film

production, and on 7 January 1907 Ole Olsen therefore bought new premises on

Gittervej, still in Frihavnen, and the film laboratory was moved here. However,

the space here gradually also became too cramped, and in 1917 the company

bought a plot of land on Redhavnsvej and had a factory building built, which

from the beginning was intended for the technical side of film production. The

new film laboratory was therefore named A/S Nordisk Films Teknik, and

here the company was housed until 1975, when it was merged with and

subordinated to the film laboratory Johan Ankerstjerne A/S, which was

located and is still located in Lygten in Copenhagen's Northwest Quarter. In

1908 there were 110 workers and workers employed in Nordisk Film's technical

department in Frihavnen.

Grandpa,

Grandma and the Movie

My grandmother and grandfather also had a very peripheral relationship with

A/S Nordisk Films Teknik, as they were for many years neighbours to a Gunner

Hansen and his wife and daughter, who also lived in Baggesensgade 24 on the

fourth floor. Gunner Hansen was the son of Edla Hansen (1883-19??), who

had already been employed at Nordisk Film in 1915, but after seven years here

she came first to Astra Film and then to Palladium. In 1924 she returned to

Nordisk Film, where she remained until 1957, when she retired. Edla Hansen was

head of the polishing room at Nordisk Films Teknik from 1936 to 1957, but

interrupted by a period from 1946-50, when she was a film editor at the studios

in Valby.

The two families were good

friends, and my maternal grandparents, who were both retired, looked after the

Hansen family's only daughter, Randi, for several years when she came from

school. Her parents both went to work and it was then almost impossible to have

her child looked after after school, because the concept of a leisure home had

not yet become a generally accepted part of schoolchildren's everyday life.

At my inquiry, my cousin Dennis

informs the following about the Hansen family: "Yes, randi too I remember,

I looked after her a lot when her mother was in a victual shop in the basement

next to "Nykro". The parents were named Asta and Gunner. Randi I have

met later, where she was married and lived in Slangerupgade. [...]"

(Dennis in letter dated 25.1.1999).

"Nykro" was the tavern located to

the left of the entrance to Baggesensgade 24. The aforementioned victual shop

was located to the left of the tavern and thus closer to Baggesensgade 26, in

fact, in the same property's front building, where my parents and I and my two

smaller brothers came to live in over the courtyard in a side building when we

moved to Copenhagen in April 1939.

En passant it can be mentioned

here that in the years 1953-55 I myself was employed in the black and white

evocation department at Nordisk Films Teknik in Frihavnen. This means that Edla

Hansen was still the head of the plastering room, as I myself worked in Nordisk

Films Teknik's evocation department during the period mentioned, which I will

tell you more about later and in the chronological order of events. At the time

mentioned here, there were considerably fewer employees in the whole house than

in 1908, but exactly how many, I do not recall, it has probably been somewhere

between 60-70 people. The lower number of employees was probably due to the

more modern technical equipment and the routine procedures introduced over

time, on the basis of which the work was carried out.

It can also be mentioned that in

the years 1959-66 I was employed by A/S Nordisk Tegnefilm, which was a

subdivision of Nordisk Films Kompagni, and which was housed in some of the

illustrious company's premises on Mosedalvej. But since all films, including

cartoons, were produced and copied out on Redhavnsvej, I had both in the

mentioned years and later my regular time at the film laboratory in Frihavnen.

And by the way, had it also had it earlier, namely around 1944-45, when Børge

Hamberg and I shot some scenes for "The Tinderbox" on the site's

already then outdated trick table. In the early spring of 1945, I had the

opportunity to use the site's newly acquired trick camera, shooting a few

scenes for a small cartoon based on Kipling's tale How the Elephant Got Its

Snable, but which I abandoned later that year and scrapped. In the summer

of 1955, I shot on the same camera and trick table some scenes for the cartoon Thumbelina,

based on H.C. Andersen's fairy tale of the same name, and which I then had

advanced plans to produce. Also, this film was abandoned before it was

finished. See about these cartoon projects later.

A Film Engineering Revolution: The Sound Film

Several different inventors made strenuous attempts to turn the silent film

into a speech film, as had already succeeded for the American inventor and

industrialist Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) as early as 1893. In 1877,

Edison had invented and constructed the so-called phonograph, which

could mechanically record and reproduce speech, song and music using wax

rollers, in which the soundtrack was deposited in the form of grooves. These

grooves were produced by a funnel, at the base of which was placed a very thin

membrane or membrane of glass or tin foil, and on the middle of the underside

of the funnel sat a small fine needle. The reproduction of the soundtrack was

done by placing the funnel with the needle at the end of the roller where the

sound grooves begin, and when the roller is then rotated at the same speed as

during the sound recording, the membrane at the bottom of the funnel is made to

vibrate exactly as when recording. These vibrations, which can be amplified via

a connected larger funnel, are perceived by the human ear as speech, song and

music.

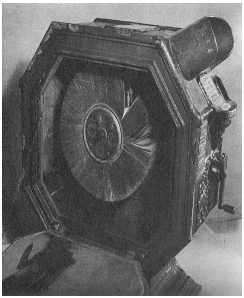

Above is an example of the so-called 'cringboxes', which very early became

a permanent 'fixture' in market places and similar places. These cringes had

different shapes and names. On the left is a so-called Mutoscope, as it looked

to the audience. On the right the same apparatus opened so that one can see the

scroll with the radially mounted series of photos of one or another situation.

The roller is mechanically connected to the handle on the front of the

appliance. By placing the head close to the binocular sight at the top and at

the same time turning the handle so that the roller was turned around at a

suitable speed, the photographs were shown to the spectator one by one in

glimpses, thereby creating the illusion or impression of continuous

movement. - © 1965 by C. W, Ceram: Archaeology

of the Cinema. Thames and Hudson. London

1965.

Edison at one point had the brilliant idea that it might be interesting to

combine the speech machine with a machine capable of recording and reproducing

moving images. And in collaboration with his closest associate, W. K. Laurie

Dickson, he first set about constructing a device, called the Cinematographer, that could record so-called moving images, which succeeded

in 1888. A few years later, in 1891, he and Dickson had also constructed a

device for reproducing moving images, and then set about recording and

combining film and sound. The device was called the Kinetoscope, but it

was still a crate-box apparatus. The combination of the two devices mentioned

and the phonograph was called the Kinetophonograph. In the

small studio "Black Maria" in Menlo Park in New York, built in

1894, Edison and Dickson then set about producing a series of short films,

which were immediately sold to the rapidly emerging American and so-called Penny

Arcades, and soon also to similar foreign "kukkasse-cinemas", including

to Pacht's Panorama & Kinoptikon at City Hall Square in Copenhagen, which only in 1896 began to show "vivid,

body-sized images". After this, it was these that were projected onto a

large, white canvas, and which could therefore be seen by many spectators at

the same time, who came to dominate the market.

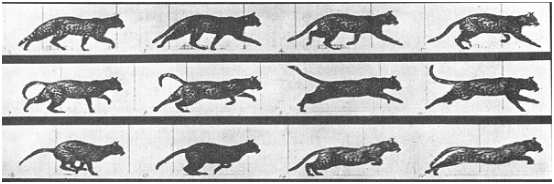

Above is a series of single photos of a cat in motion, which excellently

demonstrate the principle of the art of illusion called film. When such serial

photos are presented singly at sufficiently short intervals, the impression of

continuous movement arises in connection with the so-called 'inertia' of the

visual sense. - Eadweard Muybridge: Animals In Motion. Edited

by Lewis S. Brown. Dover Publications, Inc. New

York 1957.

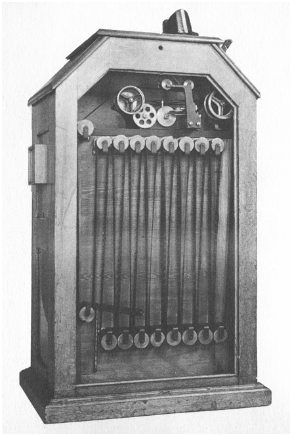

Here is Edison's

newer version of a so-called "cringe box", where the pictures in this

case are shot and shown on a film strip. The latter is suspended on a series of

coils, some of which are equipped with bars for the propulsion, which can be

done either mechanically using a crank or an electric motor. Although it is not

directly apparent from the picture, it is probably a device with a crank. At

the top is the binocular sight, through which a single spectator at a time

could watch the film. Edison patented the apparatus in 1891 under the name

"Kinetoscope". - © 1965 by C. W,

Ceram: Archaeology of the Cinema. Thames

and Hudson. London 1965.

In Denmark, two engineers, Axel

Petersen (1887-1971) and Arnold Poulsen (1889-1952), succeeded in

inventing and constructing a tone film system in which the sound was recorded

together with the image and soundtrack photographed onto the film strip itself.

This system was partly part of the tone film system that prevailed in Europe.

Petersen & Poulsen's tone film system was demonstrated in 1923. However,

speech films had already been experimented with at Nordisk Film in 1908-09, and

at the Cinema at Gl. Kongevej 100, as well as at Biorama, both places in 1909.

Biorama tried again in 1914, but it was not until Petersen & Poulsen's tone

film system, where the sound was photographed onto the film strip itself, that

the result had lasting practical applications. The system was demonstrated

through some small films that the company had produced and showcased in the

Palace Theatre on October 12, 1923.

Petersen and Poulsen had their

sound system patented so that they had the only right to do so in Scandinavia.

At that time, they entered into cooperation with Nordisk Film, which at that

time had the money changer Carl Bauder (1882-1944) as chief executive.

The latter considered that the patent

rights excluded other film companies, in particular American film companies,

from using the same system in their films broadcast on the Scandinavian film

market. It came to some lawsuits that went all the way up to the Supreme Court,

and including the American film companies' lawyers claimed that the sound

system that Petersen and Poulsen claimed to have invented had already long

since been put into general use and patented in America. The American film

companies therefore threatened to boycott the Danish film market if Bauder won

the lawsuit.

Bauder was of course aware that

it would mean cinema death in Denmark if the Americans made good on their

threats. What he wanted was only to make a financial gain by ordering the

American film companies, which used the same sound system as the one for which

Petersen and Poulsen had taken out a patent and who rented out their films in

Denmark, to pay some kind of license fee. And the case ended with American film

companies being required to pay a certain license per film of the films they

distributed on the Danish film market for the following six years.

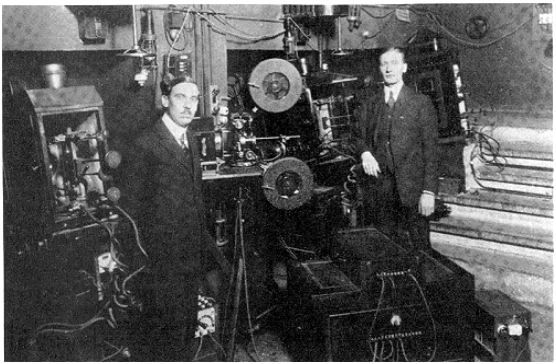

Arnold Poulsen and Axel Petersen are seen here in the Palads Theatre's

operator room in October 1923, where their tone film system was demonstrated

for the first time to a larger audience. However, the system only had a

practical lifespan of about four years, until 1927, when it was outcompeted by

American tone film systems and patents. - The Danish Film Museum's Picture

Archive.

But in the context of Petersen

and Poulsen's sound film system, one could once again find the approximately

ubiquitous Storm P. Together with the especially later famous film comedian Chr.

Arhoff (1893-1973), Storm had a revue number, a nonsense monologue, called

"Storm-and-Stille", and with this number the couple appeared in

Petersen & Poulsen's talking film 1923, which for a special invited circle

was first demonstrated in Denmark in the Palace Theatre on 12 October 1923. In

the days 20-26 October s.a., the films were shown as a pre-program for the

theater's normal, silent feature films, which, however, as mentioned, were usually

accompanied by live orchestral music.

The two engineers in the

following many years successfully sought to improve their tone film system,

which they had begun to work on developing as early as 1918. They were then

employed by the Danish company Electrical Fono Film Company, which had been

established in 1916. The company passed in 1928 to the owner of Nordisk

Elektrisk Apparatfabrik, Valdemar Selmer Trane, who renamed the film

company Nordisk Tonefilm, and who in the following time shot more than 60 small

films, some of which premiered on 4 March 1929 in the cinemas Colosseum,

Kino-Palæet, Palads Teatret and Roxy.

American film in the lead

In America, the technicians at Warner Brothers developed a tone film

system, which was called Vitaphone, and on August 6, 1926, they were able to

demonstrate the preliminary result in their own cinema in New York. The talking

films, however, were a composite program of small films, similar to Petersen

& Poulsen's demonstration in 1923. But on October 6, 1927, Warner Brothers

premiered "The Jazz Singer" with revue singer and actor Albert

"Al" Jolson (1886-1950), and although the film was only partly a

talk film with music and synchronized song numbers and a little speech, it

immediately became a huge success with the American audience. This was not

least due to the fact that in the film Jolson in a tearful voice preferred the

song to his mother, "Mammy", so that not an eye was dry with

the audience.

In 1928, Warner Bros. followed up

the success with another Al Jolson film, "The Singing Fool,"

"The World's Greatest and Most Famous Speech and Tone Movie,"

which the commercials and ads proclaimed. In it, Jolson sang "Sonny

Boy", which immediately became a world slayer. "The Singing

Fool", as the film was called in Denmark, had its Copenhagen premiere in

the Colosseum on August 17, 1929, and it was also a great success with the

general Danish audience. The newspapers' reviewers were, for good reason, a

little more critical of the not-yet-perfect speech films.

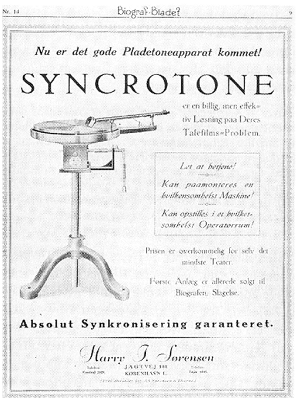

An advertisement in Biograf-Bladet no. 14, 1930/31 advertises a Harry T.

Sørensen with the record tone apparatus "Syncrotone", with which he

had some success, as by mid-1931 he had sold over 30 plants to various

provincial cinemas, which wanted to get away easily and cheaply at the

transition to tone films. However, the record tone system as such did not have

much chance of surviving the competition with optical sound systems, which

technically had the advantage that both image and sound were found on the film

strip itself.

At the same time as "The

Singing Fool", Universal Studios had the tone film "Show

Boat", "The World's Best Tone Film", Denmark's

premiere in Palads Teatret, where everything was sold out for the two evening

performances, respectively at 7 and 9.25. For the rest, the films had already

been provided with the so-called subtitles to reduce the language problem.

However, the sound side of the

films was still recorded on gramophone records, a system that lasted for some

years, but of course could not compete in the long run with the optical sound

system. Both in the USA, England and Germany, optical sound had been

experimented with since about 1900, and already then the principles of the

method were established. In the so-called optical sound recording, the sound is

recorded and reproduced by photoelectric means, and two methods are

distinguished: the intensity method and the area or amplitude method. In both

cases, sound waves via a microphone induce variations in the light beam.

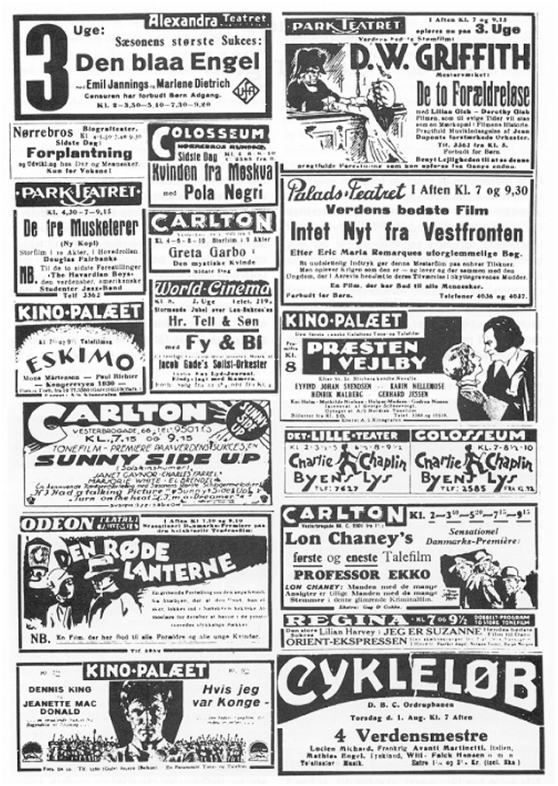

Above is a fairly representative

sample of Copenhagen cinema ads from around 1930/31, when the sound film had

been established as a phenomenon that could no longer be ignored. Even a very

hesitant Charlie Chaplin had to surrender, albeit at first reluctantly. The

Little Theatre and the Colosseum showed his The Light of the City, 1931,

which did not contain a single spoken line, but rather background music that Chaplin

himself had composed. The first Danish-Norwegian feature film with tone was Eskimo,

which premiered on 9 October 1930 in the Kino Palace. The following year in

May 1931, the same cinema showed the next Danish speech film, Præsten i

Vejlby, described as "the first Danish full-evening tone and speech

film", but otherwise it was foreign sound films – especially American

ones – that dominated the Danish cinema repertoire. – Source: Niels Jørgen

Dinnesen and Edvin Kau: The film in Denmark. Akademisk Forlag 1983, as well as The

Film's Who What Where – Danish titles and biographies. Politikens Forlag. Copenhagen 1968.

Grandma, the movie and the line of kings

Grandma has told that she had a couple of times been in Kosmorama in

Østergade and in the Cinema Theatre in Vimmelskaftet, which probably must have

happened during one of her visits to the family in Copenhagen, because when the

two mentioned cinemas were established, she was in all likelihood in the

service of a farmer near Maribo on Lolland. In any case, she has told that in

the Cinema Theatre in Vimmelskaftet in 1906 she had seen two reportage films: "Frederik

the 8th's Proclamation" and "Christian the 9th's

Funeral". She then sat in the front row of the hall, to

even see what flickered past up on the canvas. On another occasion, however,

she had also seen other of the two cinemas' more romantic film performances.

However, Grandma had more to think about than film and cinema when she found

out around May 1907 that she had become pregnant, as told earlier above.

Presumably around Christmas time of the same year, she returned to Copenhagen,

partly for the purpose of visiting the family and partly to, when the time

came, to be admitted to the Nativity Foundation. Here she came down, as already

mentioned, with her first child, my mother, on January 18, 1908. And here it

was that Grandpa came and picked them both up when they were discharged from

the foundation's birth home, to take them home with him to Lolland.

Grandma, unlike Grandpa, was

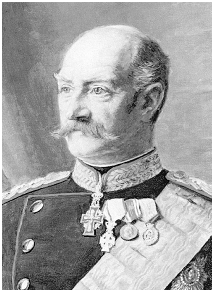

strongly royal, and there is therefore reason to look at which king(s) and

queens ruled during my maternal grandparents' lifetime. After Frederik VII's

death in 1863, Prince Christian, son of Duke Frederick of Glücksburg.m and

Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel, under the name Christian IX (1818-1906)

became King of Denmark, which he ruled until his death on 29 January 1906. On

26 May 1842 he married at Amalienborg Palace to Princess Louise of

Hesse-Kassel (1817-98), who in her later capacity as queen was called

"Europe's Mother-in-Law". Among the couple's six children were first

and foremost Crown Prince Frederik, born on 3 June 1843 in "The Yellow

Palace" in Copenhagen, where the princely couple lived at the time, and

child no. 2, Princess Alexandra, born September 1, 1844, also in "The

Yellow Palace". On 10 March 1863, the princess married the eldest son of

the English Queen Victoria, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, who under the name

Edward VII was King of England from 1901 to 1910 and Alexandra consequently

queen of that country during the same period. The Queen died on November 20,

1925.

King Christian the 9th. Queen Louise (from

Hesse-Kassel)

Christian IX's and Queen Louise's

fourth child was the previously mentioned Princess Dagmar, born 26 November

1847 in "The Yellow Palace". On November 9, 1866, in the Winter

Palace in St. Petersburg, she was married to Grand Duke Alexander

Alexandrovitsch, who in 1881 under the name Alexander III was appointed Tsar of

Russia. At the conclusion of the marriage, Princess Dagmar was given the name

Maria Feodorovna. The Tsar died on 2 November 1894, and was succeeded by his

son, Nicholas II, and his wife, Zarina Alice of Hesse. At the March Revolution

of 1917, the Tsar had to abdicate, and he and his wife and five children were

kept under house arrest in Yekaterinburg (Sverdlovsk) until in 1918 they were

brutally executed by firing squad in the basement of the property in which they

stayed, as previously mentioned.

Christian IX died as mentioned

in January 1906 and was shortly after buried in Roskilde Cathedral in the Glücksburgs'

chapel. The king was succeeded by his son, Frederik VIII, who on 28 July 1869

married Louise of Sweden-Norway, born on 31 October 1851 at Stockholm Castle.

The couple had a total of eight children, of whom Christian, born September 26,

1870 at Charlottenlund Palace, was the oldest and thus crown prince. Child

number two was Carl, born August 3, 1872 at Charlottenlund Castle. On 22 July

1896, Prince Carl married Princess Maud of England, a daughter of the later

King, Edward VII and Queen Alexandra (see above). On 12 and 13 November 1905,

Prince Carl was popularly elected King of Norway, and as was the case for his

brother, Christian X, in Denmark, he became a national rallying point during

the German occupation of 1940-45.

Queen Louise (of Sweden) King Frederick the 8th.

However, King Frederik VIII did

not get a long reign, as on a trip to Hamburg he died of a heartbeat already on

May 14, 1912. He was also buried in the Chapel of the Glücksburgs in Roskilde

Cathedral. He was succeeded by his son, Crown Prince Christian, who under the

name Christian X was to have a relatively long reign, namely until his death on

20 April 1947, which means a total of 35 years.

On April 26, 1898, Prince

Christian married Alexandrine of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, daughter of Grand Duke

Friedrich Franz III and Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna of Russia. The

wedding ceremony took place in the "Villa Wenden" in Cannes in the

south of France. Princess Alexandrine was born on 24 December 1879 at Schwerin

Castle. The royal wedding has thus taken place the same month and year as my

grandmother was confirmed in Frederiksberg Church, and as the royal person she

was, she has undoubtedly with joy and participation heard and read about the

event. Grandma later even very much appreciated especially Queen Alexandrine,

whom she even met and greeted in person, but more on this in chronological

order.

The couple had

only two sons, namely Crown Prince Frederik, born on 11 March 1899 at Sorgenfri

Palace, and Prince Knud, born 27 July 1900 in the same place. In 1947, Prince

Canute was appointed heir to the throne, as the newly appointed king, Frederik

IX, had only daughters and was therefore feared for the succession. However, by

the constitutional amendment in 1953, the line of succession was changed in

favour of female succession, whereby Princess Margrethe, born 16 April 1940,

was appointed heir to the throne.

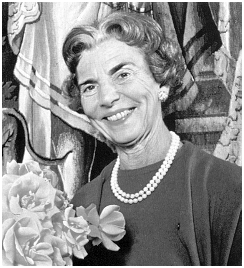

Queen Alexandrine

King Christian X

After his father's death in 20

April 1947, Crown Prince Frederik was appointed king under the name Frederik

IX. Thus, his wife, Crown Princess Ingrid, was born on 28 March 1910 in

Stockholm, the daughter of Gustav VI Adolf of Sweden and Queen Margaretha,

Queen of Denmark. The couple were married on 24 May 1935 in Storkyrkan in

Stockholm and settled at Amalienborg Palace in Copenhagen. On 16 April 1940 the

couple had their first child, Princess Margrethe, later Queen Margrethe II., 29

April 1944 Followed Princess Benedikte, and on 30 August 1946 the couple's

third and last child, Princess Anne-Marie, was born.

King Frederick

the 9th.

Queen Ingrid

The immensely popular King Frederik

IX died on 14 January 1972 of heart impairment and pneumonia at the Municipal

Hospital in Copenhagen, and a clearly grief-ridden Crown Princess was

proclaimed Queen Margrethe II of Denmark. On the 24th of the same month, the

king, like what had been the case for his parents, grandparents and

great-grandparents, was interred in Roskilde Cathedral. But neither my

grandmother nor grandfather experienced this, because they had died in 1962 and

1964 respectively and were interred at Assistens Cemetery in Nørrebro in

Copenhagen. But especially grandma had followed the later Crown Princess

Margrethe's birth and upbringing throughout the 1940s and 1950s.

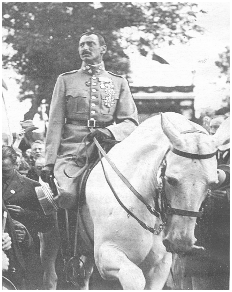

King Christian

X on horseback in 1920 Queen Margrethe II 1972

This mentions the number of kings

and queens who successively ruled during my maternal grandmother's lifetime

(1884-1962), and of course also during my maternal grandfather's lifetime

(1869-1964). We can therefore appropriately return to the mention of my maternal

grandparents' and my family relationships. More precisely, this means that in

the following we shall return to the time around my own birth.

Source for the above-reproduced portraits of the Danish

kings and queens:

The painting of King Christian the 9th is painted by H. Chr. Jensen 1887.

The portrait of Queen Louise is probably painted by the same artist. The Museum

of National History at Frederiksborg.

The painting of King Frederik the 8th is painted by Otto Bache. The

portrait of Queen Louise is probably painted by the same artist. The Museum of

National History at Frederiksborg.

The painting of King Christian X is painted by Herman Vedel. The portrait

of Queen Alexandrine was probably painted by the same artist. The Museum of

National History at Frederiksborg.

The photographic portraits of King Frederik the 9th and Queen Ingrid are

reproduced after Kay Nielsen: Denmark's Kings and Queens, Hamlet Publishing

House, Copenhagen 1980, and Lademanns Leksikon, respectively.

The picture of Christian X on horseback at the reunion in 1920 is a section

of a newspaper picture from Our History. Special

print of series of articles on the occasion of Berlingske Tidende's 250th

anniversary.

The portrait of Queen Margrethe II is a section of an official picture of

the Queen and Prince Henrik.